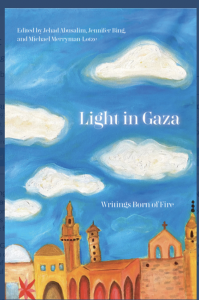

Book Review: Light in Gaza: Writings Born of Fire an anthology of Palestinian writers and artists

Maybe it was Refaat Alareer’s memory of being on a Gaza playground in elementary school. Alareer, now a professor of English at the Islamic University of Gaza, said an Israeli soldier threw a rock at him just for kicks, opening a wound in his skull.

Maybe it was the story told by Yousef M. Aljamal, a PhD candidate at Sakarya University in Turkey, of how his father, who was returning to Gaza after a day of work in Israel, was ordered to dance for the amusement of Israeli soldiers guarding the border.

I’ve read a few books, fiction and nonfiction, I’ve had to frequently put down as their writers described unimaginable indignities and disregard for human life.

But, having been raised in a Jewish family by World War II generation parents, no collection of stories has ever evoked the revulsion and respect of Light in Gaza: Writing Born of Fire, an anthology of Palestinian writers and artists, published this year by the American Friends Service Committee.

The anthology frequently cites stories of racism and cruelty by Israeli settlers, many of whom are themselves the descendants of Holocaust victims.

But the book doesn’t portray helpless victims. It honors the resistance of regular folks in Gaza, one of the most crowded regions in the world, but one of the most educated in the Middle East.

Yousef M. Aljamal’s father told the Israeli soldiers he could only dance if they clapped. When they put down their weapons and started clapping, he deftly ran away and went into hiding, his story inspiring others to challenge degrading treatment.

I’m well aware that even some of my friends will question the veracity of these stories and poems written by Palestinian intellectuals. Perhaps no other international quandary is so easily passed off as unknowable or unsolvable as what has come to be called the “Arab-Israeli Conflict.”

If you’re a Jew endorsing any criticism of the Israeli state, you are bound to be assailed for your “self-hate,” for giving voice to the anti-Semitism of Arab extremists. The richly funded American Israeli Political Action Committee (AIPAC) has been as successful as the National Rifle Association in obscuring and overcomplicating the unpleasant consequences of their uncritical public policies on guns and occupation.

The self-proclaimed true believers say that questioning the cost of the military hardware the U.S. sends to Israel is—like efforts to regulate guns—only opening the door to undermining the rights of people to self-defense. Or, worse, it’s encouraging another 9-11 terrorist attack on the homeland.

The self-proclaimed true believers say that questioning the cost of the military hardware the U.S. sends to Israel is—like efforts to regulate guns—only opening the door to undermining the rights of people to self-defense. Or, worse, it’s encouraging another 9-11 terrorist attack on the homeland.

The publication of Light in Gaza coincides with alarming political developments within Israel that could undermine claims of the so-called true believers.

Itamar Ben-Guir, for instance—a rightwing leader who was kept out of the Israeli military for his extreme hatred of Arabs—is now rising to lead Israel’s internal security. The voices of reason within Gaza, like those in this book, need to be heard and heeded.

A good read causes us not just to question our assumptions, but to dive into introspection about the source of our belief systems. When it comes to Israel and Palestine, that means revisiting my days in grey classrooms in the basement of Beth El Synagogue in West Hartford, Connecticut.

I hated Hebrew school. My father, a WWII-era Army Air Corps veteran, who spent his early childhood in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, where there were few Jews and a lot of French-Canadians, probably understood my disdain.

One year on the high holidays, when nearly every Jew in our suburb was in synagogue, we went salmon fishing in Maine. Dad looked up and said, “We’re closer to God here than the people back home in shul.” One year, when we did attend high holiday services, he spent a long time looking up, his head circling the dome above. Then he whispered, “Can you believe this synagogue has 1,200 pieces of stained glass?”

Irreverent as he was, Dad probably believed his son learning Hebrew was a fitting and necessary tribute to his best friend, Val Lapidow, from Burlington, Vt., who was killed fighting the Nazis in France. Dad’s kid needed to understand “Never Again.”

My mother, who was raised in “Little Jerusalem,” Burlington, Vermont’s tight North End Lithuanian Jewish community, recalled a classmate who asked her to show off her horns after finding out Mom was Jewish. I remember telling Mom I questioned the existence of God. She calmly reminded me that her father died when she was only seven and she needed someone to turn to. Maybe, she said, I would also see that need someday. Maybe not. It was up to me. Hebrew school might help me to decide.

I don’t remember feeling guilty about disliking Hebrew school. But, looking back, when the rationale for my being sent there was all bound up with war, death, ostracism and tradition, I must have suffered some latent pangs of regret for my scorn.

One of my Hebrew school instructors helped to reconcile my internal conflict. I remember her being my grandmother’s age. She spoke with a Yiddish accent. One day, a fly flew into the room. She gently grasped the fly in a Kleenex and let it out the window. Then, a couple minutes later she said, “We can drive the Arabs into the sea in a few days.” The divergent images are indelible.

The Arabs. I remember my grandmother coming back from a trip to Israel. My grandmother, who once worked in New York’s garment district, then owned a well-known clothing store in Burlington with her husband, said: “The Arabs are dirty.”

My parents were embarrassed by her racism. Overt racism was not appropriate. My parents had close friends who were active in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and deplored segregation. But while racism wasn’t stated, total allegiance to the State of Israel and its subjugation of Palestinian resistance was expected and respected. Bar and Bat Mitzvah gifts almost always included certificates authenticating the planting of few trees in Israel in one’s name.

The dominant narrative about Israel back then went something like this: Eretz (the land of) Israel was a hard, but promising place where bad-ass Jews were building a bulwark against any revival of Hitler or his ilk. The kibbutzim (intentional farming communities) were idyllic places where hard work and camaraderie was turning desert into rich groves of bounty. The enlightened Arabs were working with the Jews to build this new paradise. But they were undermined by mean nationalists who had been part of Hitler’s Axis. They hated all Jews and kept their own people poor and ignorant.

To be sure, there were idealists among the early settlers of the Kibbutzim, going back to the late 1800s. Many were socialists who believed Arab and Jewish workers could work in cooperation to build a democratic and prosperous society. The history of Zionism has its own internal complexities. That only makes Light in Gaza even more compelling.

It wasn’t Hebrew school, or my parents, or my rabbi (whom I later angered when I told him that the Bible was ‘good historical fiction’) that reinforced the story of Israel as an infallible victim of Arab extremism. It was the award-winning movie, Exodus, released in 1960, based on a book by Leon Uris.

I wonder how many other 10-year-old Jewish kids like me were enthralled by this movie, produced by Otto Preminger, its screenplay written by Dalton Trumbo, one of the Hollywood Ten, blacklisted during the McCarthy inquisition.

I was enchanted by the movie’s powerful Academy Award-winning score, it’s lyrics booming, “This land is mine. God gave this land to me…” The score inspired numerous covers, from Andy Williams to pianists Ferrante and Teicher, who sent the song to No. 2 on the Billboard charts. Years later, Arnold Schwarzenegger posed, and Ice-T rapped to the theme’s triumphant refrains.

The three-and-one-half hour epic centered upon the commandeering of a ship transporting 600 Holocaust survivors from a refugee camp in Cyprus through British blockades to Palestine. The master mind of the exodus was Ari Ben-Canaan, a paramilitary leader played by Paul Newman, then 35-years-old. Cast members included Eva Marie Saint, Lee J. Cobb and Sal Mineo, then 21-years-old. Sal Mineo played Dov Landau, a heroic Zionist bomb-maker who was avenging his past as a death camp inmate, forced by the Nazis to dispose of the bodies of fellow Jews.

Preminger and Trumbo deliberately softened the acrimonious relationships between Palestinians and Jews in Uris’s book, afraid of boycotts or charges of bias. Movie characters included Taha, a village chief played by John Derek. Taha, a childhood friend of Newman’s character, warns the Jews of an impending attack. He is caught and hanged by regional Muslim leader. A Star of David and a swastika are both carved into Taha’s torso.

The movie ends with Taha being buried in a common grave with a young female Zionist. In his eulogy for the two, Ari Ben-Canaan prophesized about a day when Jews and Arabs will live in peace. That theme was seductive.

Light in Gaza doesn’t counterpose the Zionist melodrama of Exodus with an uncritical, romanticized view of Palestine or the Palestinian resistance.

But the book devastatingly punctures many myths, like the one that holds that Israelis were the only people capable of transforming inhospitable desert into bountiful farms.

In another chapter in the anthology titled, “Lost Identity: The Tale of Peasantry and Nature,” Asmaa Abu Mezied describes how Palestinian Canaanites “used to grow trees and export olive oil to pharaonic families in Egypt, including the pharaonic dynasty, 2000 BC.” An economic development and social inclusion specialist with Oxfam, Abu Mezied describes the pain of Gaza farmers, driven from their land in 1948, and the consequences of Israel’s modern day agricultural policy.

Israel, she writes, has undermined Palestinian farmers who produce basic staples in favor of luxury products [like cut flowers]. This, she says, leaves the Palestinian market vulnerable to ruthless dumping and [deepening] Palestinian economic dependency on Israel.”

Not long after Exodus’s release, I won a book award for an essay that urged greater support for the state of Israel. My parents were proud. And they remained proud of my identification with Israel until 1968, when I entered George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

As the Vietnam War escalated, the campus became a prime recruitment target for the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). I paid close attention to SDS’s critique of U.S. foreign policy. The critique included an indictment of our nation’s unquestioned military support for Israel and our opposition to Palestinian rights and nationhood. I met Palestinians who were studying in D.C. They described Israel as a settler state, saying they felt an affinity to the American Indians, dispossessed of their land and marginalized by discriminatory structures, both legal and illegal.

I befriended a member of the Palestine Liberation Organization, who worked as an engineer. He said, “Look at us. We have similar skin color and facial features. Our families both value education and discipline. But we are taught to hate each other.”

For 54 years, I have been among the millions of Jews in the U.S. and even within Israel who are upset by our nation’s bi-partisan and unqualified military and political support for Israeli policies. We were incensed when, in 2015, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu audaciously violated both diplomatic protocol and simple decency by uniting with Republicans to attack Barack Obama, the sitting president, over the Iran Nuclear Deal. Most of us, I’m certain, are deeply concerned with the rightward trend of the most recent Israeli governing coalition.

After reading Light in Gaza, I’ve become more convinced that just being upset or voting for politicians who are willing to question our nation’s policies regarding Israel is not enough.

Having spent years of my life in the labor movement and supporting the struggle of people of color within the United States, I believe that peace in the Middle East depends upon honoring the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people for justice and self-determination. The writers of Light in Gaza bear witness to policies and questions I want to discuss with others.

Israel has bombed Gaza’s most celebrated library and exercises widespread censorship over educational materials. The regime’s extreme surveillance disrupts daily life everywhere, keeping Gaza’s workers awake each night as drones hover over their bedrooms. How do these policies lessen the violence that threatens people on both sides of the conflict? How does this treatment square with Jewish teachings that call upon young people to, as Jeremy Ben-Ami, the author of A New Voice for Israel, says: “repair the world, fight prejudice and injustice and ensure that others are treated as we would want to be treated?”

For me, the questioning begins with my own family. Four years ago, I attended a confirmation service at a local synagogue for my grandson, now a college junior. The service featured readings that promoted our nation’s ties with Eretz Israel. The rabbi officiating the ceremony described his pleasure in working with “smart young people” who, continuing beyond their Bar and Bat Mitzvah’s, have gained a better understanding of their Jewish faith and have vowed to keep it alive.

After the ceremony, I asked my grandson, a journalism major, if his confirmation class discussed current events in Israel. “We didn’t talk about Israel,” he said.

I’m sending my first copy of Light in Gaza to my grandson. I honor the American Friends Service Committee and the scholars who contributed to this book’s eloquence. And I thank them in advance for helping my grandson learn more about Israel and Palestine, as I did back in 1968, and with my reading of this fine book.

Len Shindel began working at Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point Plant in 1973, where he was a union activist and elected representative in local unions of the United Steelworkers, frequently publishing newsletters about issues confronting his co-workers. His nonfiction and poetry have been published in the “Other Voices” section of the Baltimore Evening Sun, The Pearl, The Mill Hunk Herald, Pig Iron, Labor Notes and other publications. After leaving Sparrows Point in 2002, Shindel, a father of three and grandfather of seven, began working as a communication specialist for an international union based in Washington, D.C. The International Labor Communications Association frequently rewarded his writing. He retired in 2016. Today he enjoys writing, cross-country skiing, kayaking, hiking, fly-fishing, and fighting for a more peaceful, sustainable and safe world for his grandchildren and their generation. Shindel is currently working on a book about the Garrett County Roads Workers Strike of 1970 www.garrettroadstrike.com.